SATAN IN THE GROIN

exhibitionist

carvings

on

mediæval churches

male genital exhibitionists on mediæval churches

HIGH-RESOLUTION PHOTOGRAPHS OF MALE AND FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS

beard-pullers

in the silent orgy

ireland

& the phallic continuum

field

guide

to megalithic ireland

the

earth-mother's

lamentation

beasts and monsters of the mediæval bestiaries

Wikimedia

slide-show of corbel figures relative to this website

click the right arrow > rather than

the left

photos are of variable quality

links

to

ENGLISH FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS ON A FRATERNAL SITE:

Ampney

Saint Peter Gloucestershire

Austerfield

Yorkshire

Bilton in Ainsty Yorkshire

Binstead Isle of Wight

Buckland Buckinghamshire

Copgrove Yorkshire

Cynghordy Carmarthenshire

Donyatt Somerset

Easthorpe Essex

Fiddington Somerset

Holdgate Shropshire

Kilpeck Herefordshire

Llanhamlach Brecon

Llanon Dyfed

Melbourne Derbyshire

Penmon Anglesey

Raglan Castle Monmouthshire

Romsey Hampshire

Royston Hertfordshire

Saintbury Gloucestershire

Stoke-sub-Hamdon Somerset

Twywell Northamptonshire

Tickhill Castle Yorkshire

Stoke-sub-Hamdon Somerset

Twywell Northamptonshire

Wimborne Dorset

Winterbourne Monckton Wiltshire

Wolston Warwickshire

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales

ANOTHER

FRATERNAL SITE FEATURING ENGLISH CHURCHES WITH EXHIBITIONISTS OR RELATED

MOTIFS AND THEIR CONTEXTS

INCLUDES :

Bilton-in-Ainsty

East Yorkshire

Bishop Wilton East Yorkshire

Bugthorpe East Yorkshire

Etton Cambridgeshire

North Grimston North Yorkshire

Nunburnholme East Yorkshire

List

and distribution map

of Irish

exhibitionists

FURTHER READING:

Jones, Malcolm

THE

SECRET MIDDLE AGES: discovering the real medieval world

Stroud,

England:

Sutton Publishing, 2002

(especially

the chapter entitled Wicked Willies with Wings: sex and sexuality in

late medieval art and thought).

PLUS

MARGINAL

SCULPTURE IN MEDIEVAL FRANCE:

towards the deciphering of an enigmatic pictorial language

Aldershot,

Hants., England:

Scolar Press.

Brookfield, Vermont, USA: Ashgate Publishing Co.

1995

ISBN 1-85928-109-5

This book, however, regards subjects such as exhibitionists and mouth-pullers as marginal - which, being on several doorways and interior capitals, they surely are not.

"This is excellent stuff. Anthony Weir's

the man when it comes to carvings of this sort. His level-headedness

and his willingness to admit that we don't know

make a refreshing change. That said, I found the witchcraft theory the

most convincing, although I also recognize - like I said - that we don't

know.

Of all the theories I've heard, this, to me, is the one that best explains the facts.

The

Sheela he's carved and buried is something very special, he's a very talented

artist (and stonemason).

That'll confuse the antiquarians of the future!"

- Tom Morrison

From

Sermons

in Stone

to the Petrified Hag

female figures

- postscript :

THE VEIL UNLIFTED

|

In 2009, British Archaeological Reports published the latest book on British exhibitionist sculptures (sheela-na-gigs, or shee-lena-gigs) under the title of: LIFTING

THE VEIL:

- a volume without an index, and with the usual terrible photo-quality of British academic books (my own included). After ploughing through the tergid text of this doctoral thesis, I am amazed that it was accepted for publication. A large part of it is a graceless trashing of all previous studies. Another chunk consists of mind-numbingly academic spreadsheets, lists and pie-charts of yet another repertoire of categories and features of the insular sheelas. Dr Oakley repeatedly condemns 'Victorian attitudes' in previous works, as well as "anti-feminism" - even accusing me of "androcentrism". But no proliferation of lists, references and obsessively-fractal categorisation (the Victorian disease of reductionism), will elucidate the enigma, nor substitute for fieldwork. Amazingly, the author not only ignores the male and bestial exhibitionists of the British Isles, but also the hundreds of both male and female exhibitionists in France and Spain. In other words, she narrows down her 'study' to a self-defined category of figures, with no reference to or comparison with earlier carvings, some of which are (as shown on these web-pages) models for later examples. The bloodlessness of her text suggests that she has never set foot in a rural French church and marvelled at the capitals; nor stood outside and seen a coherent corbel-table illustrating various sins of appetite; nor yet given thought to the iconography of Romanesque doorways which show the hellish punishment which awaits sinners.

Just as Barbara Freitag had one valuable contribution to add to the discussion of sheela-na-gigs (the origins of the word itself - see part 2), Dr Oakley has one solid idea which she doggedly pursues. This is the obvious iconographic connection between sheelas and apotropaic Gorgon-carvings - a connection which Dr Oakley insists is also functional. But she does not even try to explain why these should pop up in the British Isles and not elsewhere in Europe. Thus she fails even to approach the core of the enigma, the veil which occludes our understanding. She actually ensures her failure by her erection of an entirely unjustified distinction between sheelas (as she defines them) and other female exhibitionists, even though some Continental Romanesque church figures are almost identical and at least as 'crude', 'rude' and 'shocking' to Victorian and some modern eyes.

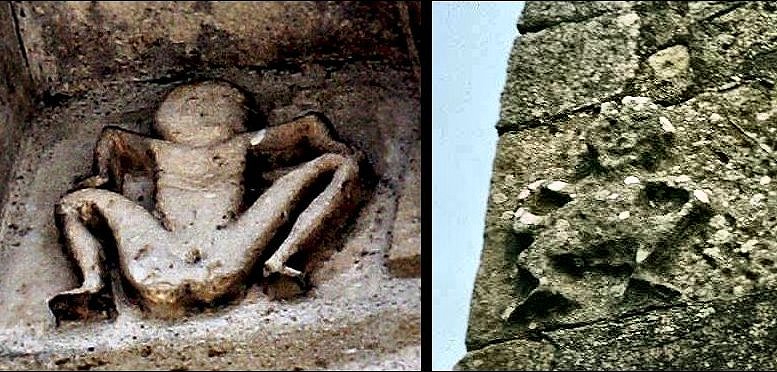

She (like Christina Weising) quite rightly draws the reader's attention to the modern confusion between the obscene (which was originally the blasphemous or seriously immoral) and the sexual, but fails to realise that this confusion dates from the early centuries of the Christian church (and, indeed, Islam). These figures were obviously designed to shock, both by their gorgon attributes (which the author dwells on) and by their sexual apparatus and/or attitude. The myth of Perseus tells us that the sight of a Gorgon transfixed the beholders (turned them to stone), thus rendering them impotent. There is, therefore, no doubt that Gorgon figures were regarded as ugly, grotesque, monstrous, arresting - nor that they fed into Romanesque iconography their monstrous appearance, their display of teeth, and their connection with snakes, which Medusa had writhing on her head instead of hair. Gorgon with protruding tongue, On the other hand, sheelas also have something in common with the (usually portable) Baubo figurines, who may or may not have been regarded as grotesque, but certainly were not apotropaic. Grotesque is an entirely subjective attribute, of course: I regard tabloid 'beauties' as grotesque, and pigs as beautiful. Other people have other opinions. At any rate, we don't know if sheelas or Baubos were regarded as ugly, monstrous or cute when they were created - after all, garden gnomes are considered cute by many! Note the large navel on this Baubo figurine

offered on eBay. While Dr Oakley follows the connection between sheelas and monsters, she does not even attempt to factor in the context of the Romanesque exhibitionists on corbel-tables - some of them extensive - where they are indisputably illustrating sins of the flesh. And in suggesting an entirely Insular upsurge in apotropaic figures, she ignores the phallic figures which we know symbolised power, property, liminality and warnings against trespass in 'Celtic' contexts. She even ignores the first male exhibitionist in a Christian context, the monk, shown in the Anglo-Saxon manuscript from the late 8th century, who clearly illustrates the temptations of the flesh.

In making an absolute distinction not only between sheelas and continental female exhibitionists on churches, but also between Romanesque insular exhibitionists and contemporaneous, continental Romanesque carvings, she puts herself beyond the Pale of intelligent research. While it is true that most Continental Romanesque female exhibitionists are feet-to-ears acrobats, whereas few post-Romanesque Insular figures are acrobatic, this merely suggests, however, that the opprobrium accorded to acrobats and entertainers in the 12th century had lessened by the 15th, so a double motif became a single one. It may also suggest a shift of function, but that is not disputed, given the length of time between the last Romanesque exhibitionists and the last post-Romanesque ones: up to 400 years. There can absolutely no doubt to anyone who has studied the corbel-tables of Aulnay, Cervatos or Mauriac, that the Romanesque exhibitionists, male, female and animal, are, primarily, minatory carvings meant to illustrate the sins most deplored by 11th and 12th century Christians - despite the perhaps unique male example at Bolmir, near Cervatos, who is making the "fig" gesture which is both obscene and apotropaic. The problem of the sheelas is that they have little or no context, and were sometimes displaced and re-used. The question of why they are where they are is the fundamental question with which I and other investigators have concerned ourselves with. Dr Oakley's book is mostly an achingly abstruse and academic divagation on the anthropology of apotropaia and the connection between the apotropaic and the sacred. But she produces no evidence to justify a sacral function for the really quite small number of sheelas on Irish tower-houses. No sane person would call them 'sacred' in the modern meaning of the word. They might be 'sacred' in the loose sense that Masonic ritual, or the turning of cure-stones might be called sacred. Indeed it is well-known that some are or were rubbed or touched during certain rituals. But a ritual is not the same as a rite. The sacred can certainly be both fascinating and repellent - like menstrual blood to some. But what is fascinating and repellent - obscene in the original sense - is not necessarily sacred. Were public executions - hanging, drawing and quartering, disembowelling - sacred acts ? Only in the widest possible sense. However, Dr Oakley does quite rightly emphasise the obvious possibility that sheelas on castles were status-symbols like phallic gateposts, or ridiculous concrete sculptures in modern gardens, or so-called swimming-pools, electronic gates, etc. - or, indeed, like good-quality carvings on churches, on which all embellishment was displayed with pride. If they were not, they would have been 'marks of Cain', 'penalty-points', stigmas or curses placed upon the castles or their inhabitants - for which there is no evidence. I have already demonstrated the similarity of some sheelas to Romanesque exhibitionists on or near the Pilgrim Roads - of which Dr Oakley unbelievably makes no mention, despite her admiration for Meyer Schapiro and George Zarnecki. My own exposure to the Romanesque figures convinces me more and more that sheela-na-gigs on castles were semi-apotropaic 'status-statues' copied to a greater or lesser extent from 'obscene' (i.e. arresting) exhibitionists in France and Spain - though not from the particular male exhibitionist at Bolmir in Spain who is 'making the fig'., nor the similar cock-snooking engraving of a masturbating male on the 14th century castle of Thouzon in France. Those on post-Romanesque churches, it seems to me, combine elements of grotesquery (like misericords, bench-ends and roof-bosses), warning of the eternal punishment awaiting sexual transgressors, and apotropaia. Dr Oakley derides 'diffusionism' (the formulation of the chief characteristic of cultural interaction). Had she stopped to think of how the Roman Empire facilitated the westward movement of artefacts and motifs from Iran, the Middle East and Egypt (and the eastward movement of motifs to India), she would have not set herself up for ridicule. In our own time the Anglo-American empires have spread ideas and artefacts right across the world in all directions. Inconsistently, she then suggests that the exaggerated-exhibitionist motif might have actually originated in Ireland and travelled from West to East, without making any attempt to substantiate the idea, or citing the one example of an Irish stone carving which could support it: the Boa Island back-to-back figures - one of which is male, and the other (assumed to be) female. Very recently, two figures have been identified on a 12th century secular building at Oakham (Leicestershire, formerly Rutland), known as Oakham Castle though it is in fact the earliest surviving hall of any English castle (1180-90) and one of the best surviving Romanesque Great Halls. Some corbels are in situ but other carvings have been inserted into 'blank' walls in a fairly random way. One of these, very badly damaged and worn, is a figure with goat's feet and one hand to its groin. It might be a female - or a masturbating male.

It so happens that elsewhere in Oakham, above the 14th century church porch, there is an acrobatic anal male exhibitionist, apparently self-fellating. This is more likely to be a salvaged, re-used Romanesque corbel rather than a copy.

After over thirty years of looking at stone iconography on Romanesque churches and at sheela-na-gigs which are continually being identified, I am convinced that the latter, on castles, are a combination of 'dirty postcard', status-symbol and apotropaia. Dr Oakley evinces no sense of humour in her 'veil-lifting', but it is hard not to smile at some of these figures. This may seem to be a modern reaction, but there can be no doubt that 12th century sculptors (whether apprentice or mature) carved them with gusto and perhaps hilarity. The little tower-house lords may also have combined humour with their pride in these carvings, whether on doorways or (almost hidden from view) high up, below barbican or crenellation.

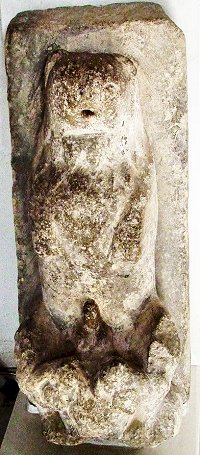

The

figure on the left is on a frieze of the 12th century church

at Saint-Vivien (Gironde), a point of embarkation from France

to Ireland and vice versa. It is a crude Romanesque example,

with the emaciation and necklessness characteristic of sheela-na-gigs. Jim

Dempsey comments on his Megalithic

Ireland website that 'I had the overall impression

that someone is enjoying a jig.'

on Ballaghmore castle in Laois. The figure at Kiltinanc church,

like that of Ballyfinboy and Ballynahinch castles are also dancing.

Romanesque figures are more often tumbling acrobatically to

illustrate the Church's condemnation of entertainers. There are examples in England also of exhibitionists closely resembling French corbel-sculptures, as at Denton in Lincolnshire and Horninghold in Leicestershire. We should also not overlook the possiblity of the unintended consequences of putting up funny little obscene carvings on churches. What might have appalled prudish monks might well have amused illiterate peasants, pilgrims and passers-by. The Irish castle figures are obviously an iconographic continuation of the church-placed figures - but there are rather few of the latter in Ireland, whereas almost all the many figures in England are on churches. The Taghmon figure is on a fortified church. Political allegiance may be relevant. All history is political. It could be (for example) that an Anglo-Norman first put one on his castle to shock the 'natives', and the custom spread. Castles are political buildings by definition, so the distribution of sheelas may well reflect shifting political realities. It is noteworthy that there are so few castle figures north of the line between Dundalk and Sligo, the last area to be pacified by the British. The Riddle of the Sheelas hinges on how a Romanesque motif of sin, carved by talented sculptors on churches with ecclesiastical permission, ended up as crude depictions of exhibitionist females on Irish castles, whereas the 'tradition' in England continued to be ecclesiastical, though with added late-medieval grotesqueness. They certainly were not celebrations of femininity or the yoni in the aggressively-patriarchal and property-based Gaelic society whose last gasp is being heard only today.

A small, undated lead amulet from Avignon,

illustrated in |

||

| ACROBATIC |

|

|

|

Over

fifty years have elapsed since I started to investigate these

figures. Since then I have visited hundreds

of sites (mainly churches) in order to create this website.

My original work

(1980) was accepted as my doctoral thesis by Prof. George Zarnecki

at the Courtauld Institute in London. Since

the arrival of the world-wide Web, hundreds of photos of exhibitionists

(male and female) and related sculptured have appeared on sites

such as Flickr and a marvellous Spanish group on Facebook.

We are now faced with an overwhelming amount of information

indicating that exhibitionists are images of sin, of Satan in

the groin and the road to Hell between the thighs, which sometimes

came to be locally displayed for apotropaic purposes in the

British Isles. |

List

and distribution-map of

exhibitionists in Western Europe

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales

|

LATEST DISCOVERY A crude late 19th century 'exhibitionist' female made out of a simple outline groove and 2 cup-marks on a rock outcrop of greywacke in county Louth (a short distance from a former railway line to Enniskillen), along with other 'sketches' including a steam engine, a ship, anchors, a mermaid, a cart, a wheel, a man pissing, a date (1888)...probably made at different times. Maybe worth comparing with Royston Cave ? see detail here from |

ESSENTIAL READING

See also:

Another Irish Sheela-na-gig Website >

also:

Las representaciones obscenas en el arte románico: entre

la vulgaridad y la apostura

https://www.academia.edu/37246446/

El enigma del Románico Erótico

https://www.arteguias.com/arteerotico.htm

Erotismo en el arte románico y medieval

https://educomunicacion.es/arte_erotico/romanico_medieval_arte_erotico.htm

BIBLIOGRAPHY

in Andersen's THE WITCH ON THE WALL (11

pdf files)

What is going on here in the Galician church of Santa María de Nogueira de Miño ?

A

very modern interpretation

of the Female Exhibitionist Motif >

Wikimedia

slide-show of corbel figures relative to this website

click the right arrow > rather than

the left

photos are of variable quality

![]()

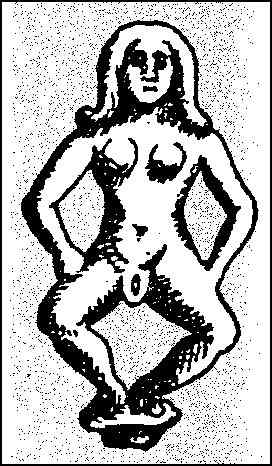

Finally,

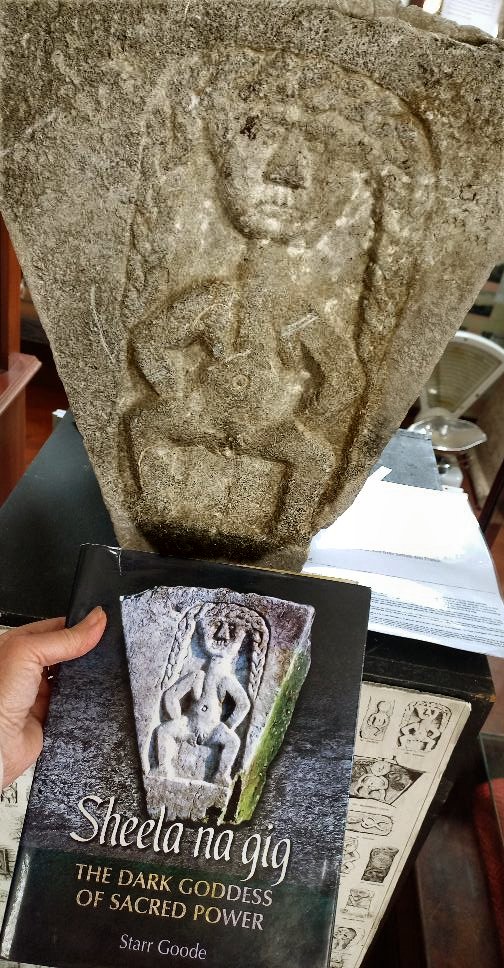

BEWARE OF BOOKS LIKE THIS

They are as bogus as this figure I carved in 1978.

*

This

site has been enhanced by FloatBox